Chang’s new broom sweeps briskly throughout her book, and she clears a lot of ground. In the epilogue, the author describes Cixi’s legacy as “towering” and says she “brought medieval China into the modern age.” Praising her as a consensus seeker, she says that “her rule was benign” - at least compared with her predecessors’ regimes. Chang ends with descriptions of Cixi’s final years, when she welcomed Western women into her court and issued progressive edicts, including plans for voting rights. Though she does not condone Cixi’s support of the Boxers, she is an apologist for it. Never short of narrative energy, she moves swiftly on from Cixi’s more unpleasant dealings - having a concubine shoved into a well, for example. Her new book takes on the turbulence of late-19th-century China, tracing competing court interests, rival political ideas, foreign attacks and Cixi’s responses.

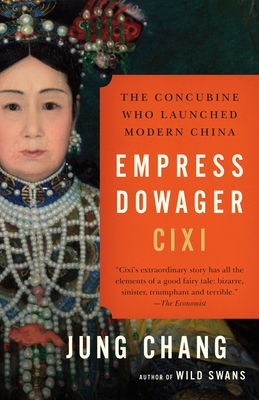

Jung Chang is the author of “Wild Swans,” a 1992 best-seller recording the lives of her family in Communist China. During her last six years, she pursued reform policies, and developed friendships with Western women - association with men being impossible because technically she was still in the harem. The results were disastrous, as she admitted in a statement of remorse.

It fell to her to cope with war with Japan and the Boxer rebellion, during which she battled against no less than eight foreign countries. After he became the Emperor Guangxu, she retained an advisory role that quickly blossomed into full control. When her teenage son died after ruling only briefly, she appointed a nephew as heir apparent, and once more ran the government. Protocol insisted that Cixi had to issue orders from behind a yellow screen to avoid being seen by men, but nonetheless she got down to business and developed commerce with the West, which generated revenues for China. Xianfeng appointed regents for his young son, but since all were proponents of his disastrous policies, Cixi hatched a coup to replace them with herself and the empress as joint empress dowagers. In 1861, Xianfeng died, having unsuccessfully battled both the Taiping rebellion and the British and French, who wanted him to open ports to their ships. Though she was chosen, she won no special favor until four years later, when she gave birth to his first-born son, and then rose rapidly through the harem hierarchy until she was second only to the Empress Zhen. In a fascinating account of Chinese customs, Jung Chang explains that as the daughter of a wealthy Manchu family, Cixi was one of hundreds of girls sent for inspection by Xianfeng as potential concubines.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)